Gait analysis of an elite runner

“The 3D gait analysis is an incredibly useful exercise, and has helped to flag up issues with the way I move that might eventually lead to injury. To maintain consistent training it’s really important to avoid problems before they arise. I hope this session should hopefully help me avoid time on the physio’s couch in the future!

The guys have also pinpointed a few areas to for me to work on which should help improve performance. I would highly recommend this to other runners who are looking to knock some time off their PB’s.”

Shaun Dixon

UK Fell Running Champion

Barefoot running – the debate rages on

Although there has been a drop off in the number of runners using the barefoot approach, the lack of evidence either way in this field means the debate will continue. The recent publication of the results of an online survey has re-ignited this debate with analysis and subsequent comments on the excellent blog produced by Craig Payne (http://www.runresearchjunkie.com/barefoot-running-survey-evidence-from-the-field/).

In my opinion, the type of shoe required is in part determined by the underlying structure but, as importantly, the interaction of the whole lower limb / pelvis. Someone with a mildly pronated foot type may pronate more due to poor overall limb control and benefit from a shoe with stability. However, this is addressing the symptom not the cause. Improve the function and you may reduce the need for stability. By contrast, someone with a significantly pronated foot type is likely to require more support. Transitioning to a different foot strike pattern has the dual possibility of either reducing or increasing injury risk / rate.

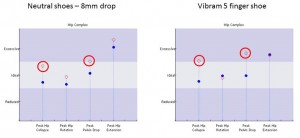

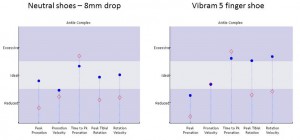

The example gait below shows a physical fitness trainer who is very keen on the barefoot approach for himself. The ankle results show a reduced degree of peak pronation and slightly increased time to peak pronation as would be expected with a forefoot strike. However, you will note that the asymmetry present in a neutral shoe with 8mm drop is still present barefoot and, if anything, is worse in terms of tibial rotation. Thus we can change things by going to barefoot but not necessarily improve function.

Barefoot running, as expected, reduces peak pronation and time to peak pronation but does not resolve the asymmetry which, if anything, gets worse in terms of tibial rotation. Click on picture for enlarged copy.

More importantly the hip / pelvic values clearly show that the altered demands of barefoot running require greater hip control which he clearly does not have. One can only assume this places him at more risk. So, in his instance, a more traditional running pattern / shoe may be a better option unless he addresses the muscle imbalance to allow the altered running style. However, he may be able to keep with this dysfunction to a certain level of activity. Past this level and with increasing fatigue, the risk of injury increases. This can be moderated by a structured approach to increasing activity levels (i.e. a graduated load response) but, intuitively, there will be a maximum threshold after which injury is more likely. Of course we also need to consider all the extrinsic factors such as running surface etc.

Thus which shoe and which style an individual utilises will depend on their overall function both structurally and dynamically. My current approach with patents is to optimise function as much as possible with structured rehabilitation programmes and then determine the level of support or gait modifications that may be required to minimise injury. If they are unable or not prepared to do the necessary work to achieve this then they have to accept that their function is a compromise and they may not be able to exercise to their desired level without injury. However, we hope that we can at least educate in this regard and thus allow them to make an informed decision in terms of training and exercise levels.

It is less about extremes and more about a balanced approach, optimising function and then managing around individual limitations. Therein lays the skill as one size does not fit all.

Call 020 8502 1777 or

Call 020 8502 1777 or  online form

online form