- March 2016 (1)

- November 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (1)

- January 2015 (1)

- July 2014 (2)

- June 2014 (1)

- May 2014 (1)

- April 2014 (2)

Plantar fasciitis or plantar heel pain syndrome?

If you have or have had plantar fasciitis, please take our survey.

Let us know your experience and find out the results here.

It is all too easy to label all heel pain as plantar fasciitis and is better termed plantar heel pain syndrome as there are a number of factors that can contribute to pain. In this short blog we explain the range of conditions that can occur.

Firstly, the term plantar fasciitis has be questioned as there are no classic features of inflammation (the ‘itis’ in fasciitis) but there are features of degeneration (Hossain & Makwana 2011). As a result some prefer to term this plantar fasciopathy.

Whilst an ultrasound scan is considered the primary investigation by many (these generally show thickening and ruptures), Abdel-Wahab (2008) demonstrated that a wider range of pathology was observed on MRI.

This case is an example of why I feel an MRI scan is far superior to an ultrasound scan and allows identification of the pathologies that may be present in these patients. Accepting that an ultrasound scan is more cost-effective and if available during consultation, much more immediate, it cannot provide the extent of pathology.

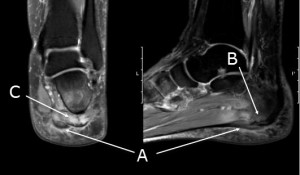

Plantar heel pain syndrome; Thickening of plantar fascia with intrasubstance signal (A), bone marrow oedema (B), intrinsic muscle oedema (C)

In the case demonstrated, there is soft tissue oedema both deep and superficial to the plantar fascia, there is inflammation within the intrinsic muscles, thickening and inflammation within the fascia itself and bone marrow oedema. There is no significant change within the intrinsic muscles on T1 and thus no fatty infiltration, as has been described with nerve compression (Chundru et al 2008). In my opinion, plantar heel pain syndrome results in the inflammatory changes which in turn irritate the nerve and then progress to muscle degeneration.

This patient had been placed on a standard conservative management package which included footwear, strapping, ice, stretching and off-the-shelf orthoses. Whilst there had been some benefit, symptoms persisted hence the MRI scan. The presence of bone marrow oedema indicates the need for greater shock absorbency/redistribution and she was therefore provided a modified orthotic which again has been helpful.

The options for further treatment include a guided steroid injection although one may wish to target both deep and superficial to the fascia and in this instance, I would combine this with a two week period of immobilisation in a walking boot. However, the injection will not affect any symptoms from the bone oedema. Shock wave therapy can be used in the presence of bone oedema although the nature of action is not well understood.

Whilst the risks are small, a steroid injection does run the risk of fat pad atrophy/fascial rupture whilst the risks with shock wave therapy are minimal, if any at all. In this instance, the patient can be counselled regarding the relative merits and be aware of why there may be potential residual symptoms irrespective of the treatment modality chosen.

Clearly, the initial diagnosis of plantar heel pain remains clinical and the availability of ultrasound in clinic allows an immediate and cost effective method of assessing for a thickened fascia. However, in the absence of thickening or a more chronic, unresponsive case, MRI allows more accurate assessment. It can identify the location of any inflammatory changes and a targeted injection for which ultrasound is the technique of choice. The presence of bone oedema requires modification of orthoses and is an indication that the condition may take longer to settle. Shockwave therapy is an option for all cases although may be the treatment of choice where there is little evidence of soft tissue oedema and / or the presence of bone marrow oedema or as an option when injection therapy has failed. It is generally recommended when there has been 3 months of failed conservative care.

References

Call 020 8502 1777 or

Call 020 8502 1777 or  online form

online form